The 19th century saw the emergence of the profession we would consider “landscape architecture” today. One of the first was Humphry Repton, an Englishman who not only started the phenomenon of actually using flowers as design elements (more on that at the end), but also perfected the art of PR through illustrated business cards and his famous “Red Books.”

The 19th century saw the emergence of the profession we would consider “landscape architecture” today. One of the first was Humphry Repton, an Englishman who not only started the phenomenon of actually using flowers as design elements (more on that at the end), but also perfected the art of PR through illustrated business cards and his famous “Red Books.”

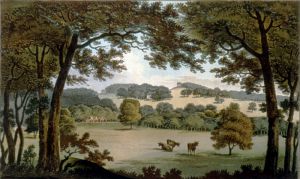

The illustrated books showed potential clients their property as is, and how it could be, if they hired him. Not only was this an amazing feat of advertisement, but construction as well, since the “after” landscape was revealed when built in flaps on the book were removed. And when Repton had free time, he added non commissioned ideas to a general collection called Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening that was eventually published

Coincidentally, it was around that time that actual literature on gardening and landscaping began to crop up everywhere. This was telling of the garden’s dissemination into popular culture as not just a thing for the rich, but for the people. It’s also around then that editor of The Brooklyn Eagle, Walt Whitman proclaimed “We need parks!” (Or something along those lines…) A major reason for this growing public outcry was because it was becoming increasingly considered “unclean” for people to picnic in cemeteries, which is what they had been doing when needing a bit of picturesque green.

It’s also around then that editor of The Brooklyn Eagle, Walt Whitman proclaimed “We need parks!” (Or something along those lines…) A major reason for this growing public outcry was because it was becoming increasingly considered “unclean” for people to picnic in cemeteries, which is what they had been doing when needing a bit of picturesque green.

The first deliberately designed public park (as opposed to a redesign of a formerly rich-only hunting park a la Tiergarten in Berlin) was Birkenhead in Liverpool, by Sir Joseph Paxton (who also designed a little building known as the Crystal Palace, which influenced the invention of greenhouses everywhere). His winding paths through various terrain were different based on whether he envisioned someone traveling on foot or by carriage. These ‘lawns for the city” were enthusiastically embraced by an ever-growing working class population in need of relaxation.

An important designer in the pro-park movement was Hudson Valley based Andrew Jackson Downing, the son of a horticulturist who grew up with an intense appreciation for nature and the beliefs that everyone should be equally educated about botany, gardening, etc. Not only did he design the landscaping for the DC Smithsonian and the White House lawn, but, if he hadn’t died prematurely in a freak steamer accident, his loose proposal for a New York City park would have surely evolved into the official design for Central Park.

As most (NYC) people know, the designer for that patch of green ended up being Frederick Law Olmsted, who entered his idea, entitled “Greensward” into the Central Park public call for entries. The rules were that the designs had to include 2 resevoirs and 4 transverse roads.

The idea for sunken roads is what won it for Olmsted – apparently the judges agreed that nature should be as uninterrupted as possible. Although Olmsted took that idea even farther by disapproving of most proposed statues and structures for the park, including the Met. He obviously lost the battle on that one, so when he got around to designing Prospect Park (around the pesky delays of the Civil War), he set aside space for the Brooklyn Museum so it wouldn’t impose on his designs.

For numerous reasons, Olmsted considered Prospect to be the more successful of the two commissions. And I agree!

With the emergence of public parks designed by professionals came housing developments designed by city planners. The Garden City Movement was the taking of those meandering paths of the park, and turning them into the roads of suburbia, with the interconnected lawns representing a park…that you live in. Early developments are best represented through Riverside, outside of Chicago, which was designed by (surprise!) Olmsted, and Forest Hills, in Queens, designed by (again!) Olmsted Jr.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE